How was "personhood" redefined in the 18th & 19th centuries?

Scroll down below to read about each definition of personhood to learn more!

5 Definitions of Personhood

Legal

A legal understanding of personhood comes from looking between the lines of the laws and policies established by governments in the Atlantic world during the 18th and 19th centuries. There were no thorough written codes defining what made a “person.” But from the laws that existed and from secondhand accounts about slavery, we may infer that slaves had no legal right to marry, keep titles, or testify in court—legal rights belonging to people.

Above is a picture of the original copy of the law passed in Pennsylvania in 1780 for the gradual abolition of slavery.

Above is a picture of the original copy of the law passed in Pennsylvania in 1780 for the gradual abolition of slavery.

Before the fourteenth amendment to the constitution of the United States was added in 1868, blacks held no legal rights in the country. George M. Stroud noted that slaves “had no head in the state, no name, title or register; …they had no heirs, and therefore could make no will." Furthermore, slaves were not “entitled to the rights and considerations of matrimony, … nor were they proper objects of cognation or affinity, but of quasi-cognation only." Though this was a description of Roman civil law, the condition of slavery in the United States was only a “little” better. Stroud continues by claiming “the cardinal principle of slavery,--that the slave is not to be ranked among sentient beings, but among things—is an article of property—a chattel personal,--obtains as undoubted law in all of these states." But Stroud also notes that there are no succinct, written codes on the matter of slaves and their personhood.

Though there were attempts to abolish slavery, the language of the laws did not group slaves or people of color within the realm of personhood. One law passed in Pennsylvania in 1780 for the gradual abolition of slavery—one step closer to “universal civilization”—says, “That all persons, as well Negroes and Mulattoes as others, who shall be born within this state from and after the passing of this act, shall not be deemed and considered servants for life, or slaves." Grammatically, Negroes and Mulattoes were a group placed within a parenthetical phrase behind “persons,” as if an afterthought. This placement seems to indicate that slaves and those with differences “in feature or complexion” were not considered people, at least by law.

Though there were attempts to abolish slavery, the language of the laws did not group slaves or people of color within the realm of personhood. One law passed in Pennsylvania in 1780 for the gradual abolition of slavery—one step closer to “universal civilization”—says, “That all persons, as well Negroes and Mulattoes as others, who shall be born within this state from and after the passing of this act, shall not be deemed and considered servants for life, or slaves." Grammatically, Negroes and Mulattoes were a group placed within a parenthetical phrase behind “persons,” as if an afterthought. This placement seems to indicate that slaves and those with differences “in feature or complexion” were not considered people, at least by law.

Above is a picture of the original copy of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Above is a picture of the original copy of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Other laws made slavery a legal status. Eric Foner said the Constitution of the United States made slavery a national institution with a clause saying a fugitive slave must be returned to the South if captured in the North. “Even though the northern states could abolish slavery, as they did, they still could not avoid their Constitutional obligation to enforce the slave laws of the southern states. A fugitive slave carried with him the legal status of slavery, even into a territory which didn’t have slavery.” The Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, “which made the federal government responsible for tracking down and apprehending fugitive slaves in the North … and sending them back to the South”, stripped the rights from freed slaves or freemen. The law said that local courts could not adjudicate whether a person was a slave or not. It was federal commissioners who would come in and hear testimony. And the slave was not allowed to testify. It was the testimony of the owner, or the person who claimed to be the owner, of this alleged fugitive. And the commissioner would judge whether the owner’s testimony was believable or not, and then send—as they usually did—the person back to slavery.” Even those who were “free born” were subject to losing their rights by being banned from testifying.

In general, legal personhood is defined by the rights that are denied to slaves and former slaves.

In general, legal personhood is defined by the rights that are denied to slaves and former slaves.

Political

Concepts of personhood are incorporated in the political and cultural context. To claim one’s personhood requires social recognition. The fact is, however, throughout history certain groups have been treated differently by a system that denied their humanity, stripped them of their personhood, and subjected them to suffer misery and horrors beyond measure.

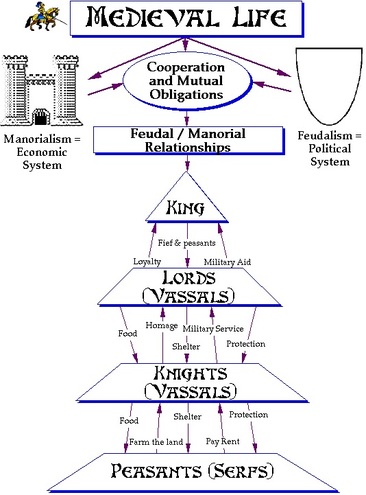

In the ancient and medieval world, unequal and hierarchical systems are the norm and ethnic hierarchies are unremarkable, since this is the general structuring principle of the social order. During medieval times (approximately the 5th to 15th century), the political hierarchy was more of a feudal system where there were royalty and nobility (e.g. kings, queens, monarch, and barons), the aristocracy (e.g. lords and knights), and the peasants (serfs). This basic political hierarchical structure stayed in essences into the 16th and 17th centuries, but the introduction of a slave system where the enslavement of Africans became a prominent feature in the Atlantic world. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the political system in its most basic form boiled down to citizens (kings and everyone else) and slaves.

In the ancient and medieval world, unequal and hierarchical systems are the norm and ethnic hierarchies are unremarkable, since this is the general structuring principle of the social order. During medieval times (approximately the 5th to 15th century), the political hierarchy was more of a feudal system where there were royalty and nobility (e.g. kings, queens, monarch, and barons), the aristocracy (e.g. lords and knights), and the peasants (serfs). This basic political hierarchical structure stayed in essences into the 16th and 17th centuries, but the introduction of a slave system where the enslavement of Africans became a prominent feature in the Atlantic world. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the political system in its most basic form boiled down to citizens (kings and everyone else) and slaves.

Whether people are divided into citizens and slaves, or lords and serfs, the status of the estate determines one’s life course from birth to death. In the 18th and 19th century Atlantic world, the American and French Revolutions declared that all men are created equal with “people” recognized as morally equal individuals. In the New World, the individual becomes the central object of value, so that government can be justified with respect to the consent of these individuals, a socially recognized personhood.

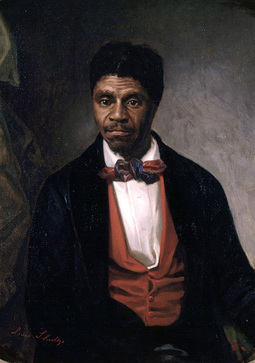

Above is a painting of Dred Scott, painted by Louis Schultze in 1882.

Above is a painting of Dred Scott, painted by Louis Schultze in 1882.

During the peak of the Atlantic slave trade, economic factors affected the social systems as the demands of the mass production of commodities such as sugar, coffee, and tobacco, forced millions of Africans to become the source of slave labor. Slaveholders elevated themselves by dehumanizing and excluding enslaved Africans from the social order. In the absence of social recognition, rights for salves did not exist, and without social recognition they became less-persons persons with the loss of their personhood.

The 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Dred Scott vs. Sandford judged blacks as “beings of an inferior order” with “no rights which the white man is bound to respect,” so that “the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit,” this being “an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing.” With inhuman bondage and unrecognized personhood, political slavery became the embodiment of Africans identity in the 18th and 19th century Atlantic world and hardly anyone or anything untouched by it, until emancipatory freed bondage and personhood is universally recognized in the 20th century.

The 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Dred Scott vs. Sandford judged blacks as “beings of an inferior order” with “no rights which the white man is bound to respect,” so that “the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit,” this being “an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing.” With inhuman bondage and unrecognized personhood, political slavery became the embodiment of Africans identity in the 18th and 19th century Atlantic world and hardly anyone or anything untouched by it, until emancipatory freed bondage and personhood is universally recognized in the 20th century.

Religious

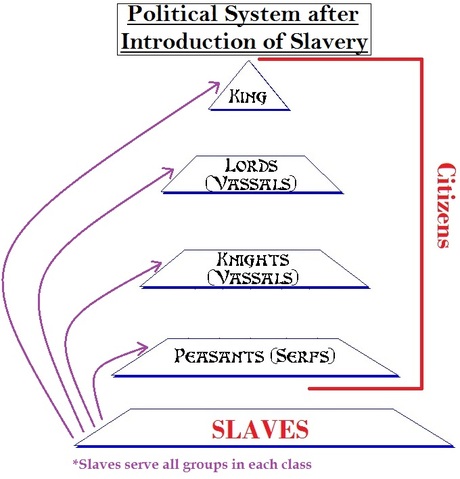

Religion is arguably the most important category of how Europeans defined themselves across centuries and one of the most important rubrics for how they saw others as well (Wheeler 15). To gain personhood within a religion, namely Christianity, one must first be able to not only understand the message of the Bible but also read it on one’s own. This particular caveat comes from the time of Martin Luther and the split from the Catholic Church, a time when all the religious authority was held by the Roman Catholic Church. From this point, religious authority was taken away from the clergy and given to the individual. In the United States, according to George Stroud’s book, there were a number of laws based on the thought that Negroes were “beings, ignorant of letters, unenlightened by religion, and deriving but little instruction from good example” and were therefore incapable of ever truly being a person (99).

But

as Stroud also points out “the knowledge of its precepts and promises

will promote the happiness here and hereafter of every accountable

creature” (91) which included slaves yet masters were trying to prevent

slaves from enjoying the access to gospel. In essence, these masters

were denying the slaves the ability to gain religious personhood.

Religious personhood was a powerful tool that many educated and/or free African slaves quickly began to use and understand. Equiano’s narrative is full of Christian-fueled arguments that appealed far more greatly to religious white people and Europeans than simply arguing for the wrongness of slavery on the basis of ‘natural rights’. It was a common ground loaded with easily recognizable set of morals that denounced slavery. Equiano was using a tool that he had gained from slavery to combat the very thing that had introduced it to him. But that does not mean would had to be free to gain religious personhood, just that it was a highly effective tool to both get and stay free. Revered Noah Davis’ father was a religious man that attended church every Sunday and could recite portions of the Gospel from memory alone, yet he was a slave all of his life. Davis’ father could not read but he understood the power of the Bible. Religious personhood was a powerful tool not only as a slave but as a free man.

Religious personhood was a powerful tool that many educated and/or free African slaves quickly began to use and understand. Equiano’s narrative is full of Christian-fueled arguments that appealed far more greatly to religious white people and Europeans than simply arguing for the wrongness of slavery on the basis of ‘natural rights’. It was a common ground loaded with easily recognizable set of morals that denounced slavery. Equiano was using a tool that he had gained from slavery to combat the very thing that had introduced it to him. But that does not mean would had to be free to gain religious personhood, just that it was a highly effective tool to both get and stay free. Revered Noah Davis’ father was a religious man that attended church every Sunday and could recite portions of the Gospel from memory alone, yet he was a slave all of his life. Davis’ father could not read but he understood the power of the Bible. Religious personhood was a powerful tool not only as a slave but as a free man.

Economic

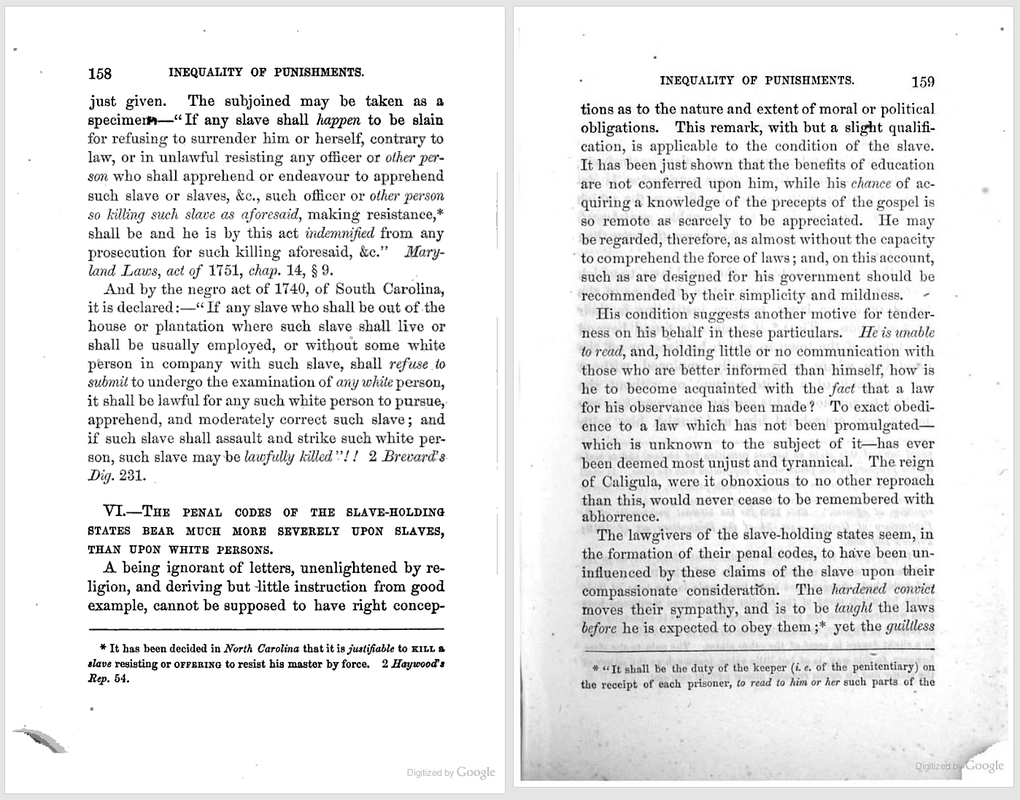

The early modern Atlantic slave trade has long been recognized as a central feature of global economic history. Economic factors have long been a defining point in the slave trade, but more importantly, economic factors defined personhood in the 18th and 19th centuries. African slaves were bought and sold like objects in the global commodity chain. The processes of the global commodity chain include the growing of a product, the transport of a product, the distribution of the product, and the consumption of that product once it reaches it’s final destination and ready for consumption—slaves underwent the entire series of processes in which something becomes a finished product in the hands of a consumer. This treatment of slaves as global commodities is the very backbone of the idea that slaves were seen as less than people or having any personhood.

Slaves were goods and could be “sold, transferred, or pawned as goods or personal estate” and they were esteemed as such.

They were seen as object for the use and transformation of European’s liking in mere economic transactions. Europeans and Anglo-Americans buying slaves were often given receipts of purchase upon trade. What is interesting here is that on the receipt there is a blank space that indicates the use of a pronoun for the slave. The receipt below says, "[I] warrant and defend against the claims of all persons whatsoever, and likewise warrant [him] sound and and healthy in mind and body, and slave for life." The fact that slaves were considered property and used in business transactions but Europeans still felt as though they needed to distinguish between gender further illustrate this para-human status and clearly defines the economic boundaries of personhood.

Slaves were goods and could be “sold, transferred, or pawned as goods or personal estate” and they were esteemed as such.

They were seen as object for the use and transformation of European’s liking in mere economic transactions. Europeans and Anglo-Americans buying slaves were often given receipts of purchase upon trade. What is interesting here is that on the receipt there is a blank space that indicates the use of a pronoun for the slave. The receipt below says, "[I] warrant and defend against the claims of all persons whatsoever, and likewise warrant [him] sound and and healthy in mind and body, and slave for life." The fact that slaves were considered property and used in business transactions but Europeans still felt as though they needed to distinguish between gender further illustrate this para-human status and clearly defines the economic boundaries of personhood.

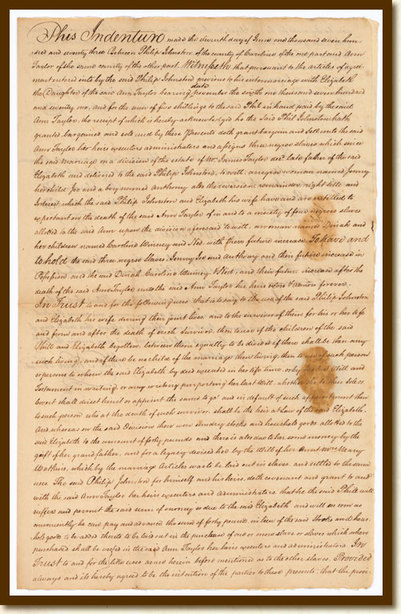

Above is a dowry listed "three negroes" for a man named "Philip Johnston and his wife Elizabeth.

Above is a dowry listed "three negroes" for a man named "Philip Johnston and his wife Elizabeth.

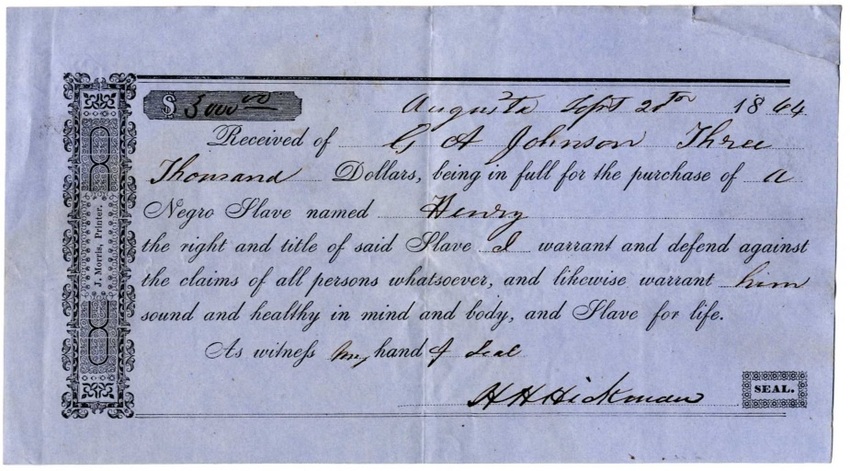

The African slave trade was a profitable economic activity for both sellers and buyers. Manning says that buyers could offer to buy a slave for more than the value of its production in African agriculture, and the deal would be profitable for both parts since slaves would be put to work using the advanced, plough-based agriculture. When put in this context, African people simplified in worth by dollar amounts rather than humanistic qualities or skills (Angeles 6).

For example, Britain started expanding its sugar industry in the Americas at the end of the 17th century, from about 1674-1699. The cost of a slave during this time was £19.61 (approximately $30 U.S. dollars). This price bought about 25 years of work from the slave (Angeles 9).

Not only were slaves exchanged for currency, but they were often used as forms of currency. Dowries and wills typically leave money or possessions for different people after the death of the person writing it. For example, the dowry gift from Ann Taylor (pictured to the left) said that “three negroes,” named Jenny, Joe, and Anthony, were “entitled” to Philip Johnston and his wife Elizabeth “expectant on the death of … Ann Taylor.” The use of slave's names in the dowry also shows that slaves were seen as para-human or less than human but still considered as forms of currency in the 18th and 19h centuries.

For example, Britain started expanding its sugar industry in the Americas at the end of the 17th century, from about 1674-1699. The cost of a slave during this time was £19.61 (approximately $30 U.S. dollars). This price bought about 25 years of work from the slave (Angeles 9).

Not only were slaves exchanged for currency, but they were often used as forms of currency. Dowries and wills typically leave money or possessions for different people after the death of the person writing it. For example, the dowry gift from Ann Taylor (pictured to the left) said that “three negroes,” named Jenny, Joe, and Anthony, were “entitled” to Philip Johnston and his wife Elizabeth “expectant on the death of … Ann Taylor.” The use of slave's names in the dowry also shows that slaves were seen as para-human or less than human but still considered as forms of currency in the 18th and 19h centuries.

Social

A social definition of personhood is perhaps one of the hardest to narrow down to an easily understood notion. It involves the overlaying of various cultures, which are often conflictory at the very basic of levels, and often leads to one culture becoming the dominant. And by dominate we simply mean the one who defines how both cultures are expressed within this overlaying. This was the case with the African slave trade, in which the various African cultures were prevailed over by the technologically advanced European cultures. As seen in the ledger from Humphry Morice’s ship, slaves were reduced to a mere commodity that was only worth an amount as dictated by their health and age. There is no separation by tribe or language, as Africans separated themselves. The Middle Passage funneled these diverse cultures into a single European defined identity of African.

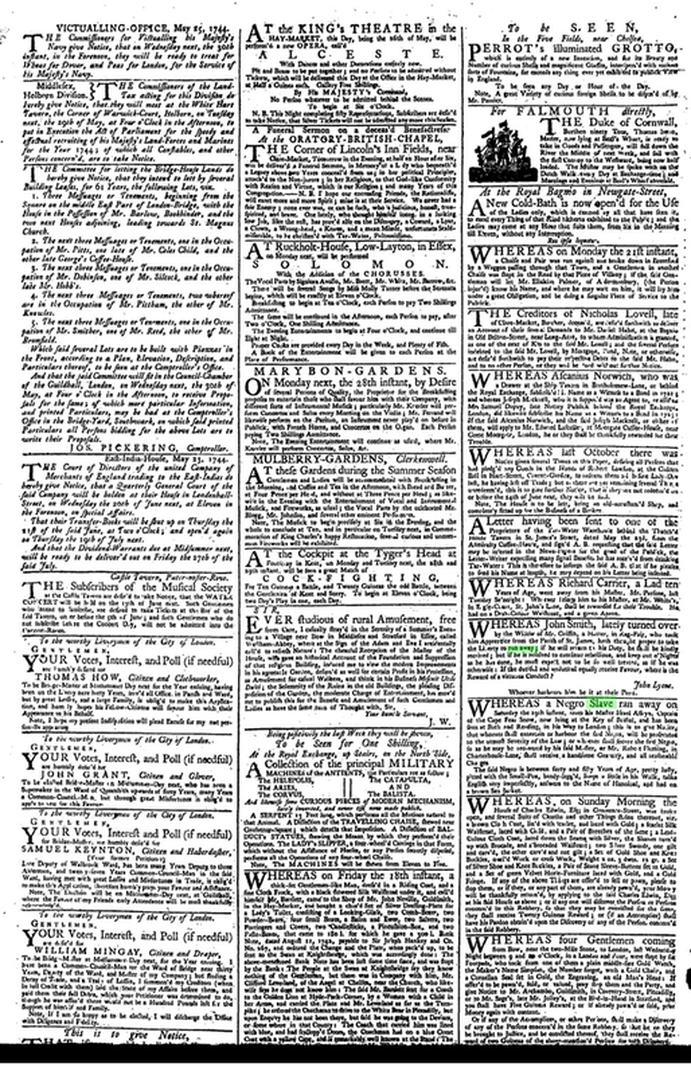

Above are advertisements in the Daily Advertiser. One advertisement has a description for a runaway slave that "answers to the name of Hannibal."

Above are advertisements in the Daily Advertiser. One advertisement has a description for a runaway slave that "answers to the name of Hannibal."

The

easiest way to understand the social definition of personhood and just

how illusive it is to gain, is an example pulled from the slave

narrative of Equiano. Equiano recalls the instance where Joseph

Clipson, a free young mulatto man, was sailing on the ship that Equiano

was on. A white captain from Bermuda came onto the ship and claimed

that Clipson was still a slave and demanded he be taken back to

Bermuda. Clipson pulled out his birth certificate to show that he was

actually a free man but it did not work. Clipson was taken off the ship

and sold as a slave. While this incident confirmed Equiano’s fear of

never been truly free, it shows for our purposes that though Clipson had

legal and economical personhood on his side, the social circumstances

he was in subsumed all the rest to define him as not a person.

Combine this instance with the language used about slave and blacks of the time and the situation only gets murkier. This is seen in the classified ad for the runaway slave in the Daily Advertiser that says the runaway slave “answers to the name of Hannibal” rather than saying his name is Hannibal.

This is how someone today would advertise for a lost pet, rather than a lost person. Social personhood is the most difficult aspect to gain with regards to our spectrum. It depends on have legal rights, often gained through political activism and religious understanding, as well as loss of an economic role of commodity through entering the system as a player rather than a piece. This makes it the most difficult to discern within the slave narratives we have chosen to focus on.

Social personhood is not a term than can simply be defined by searching through a few documents and picking out instances that are particularly striking. Social personhood requires for the individual to have passed through many tests before he or she encounters the final test: the social recognition by peers and culture. It is not a moment that can be pinned down and occurs often, with each new encounter of various subcultures contained within the larger dominant culture.

Combine this instance with the language used about slave and blacks of the time and the situation only gets murkier. This is seen in the classified ad for the runaway slave in the Daily Advertiser that says the runaway slave “answers to the name of Hannibal” rather than saying his name is Hannibal.

This is how someone today would advertise for a lost pet, rather than a lost person. Social personhood is the most difficult aspect to gain with regards to our spectrum. It depends on have legal rights, often gained through political activism and religious understanding, as well as loss of an economic role of commodity through entering the system as a player rather than a piece. This makes it the most difficult to discern within the slave narratives we have chosen to focus on.

Social personhood is not a term than can simply be defined by searching through a few documents and picking out instances that are particularly striking. Social personhood requires for the individual to have passed through many tests before he or she encounters the final test: the social recognition by peers and culture. It is not a moment that can be pinned down and occurs often, with each new encounter of various subcultures contained within the larger dominant culture.